The Signal & The Noise: Why True Connection Requires More Than Clicks

Online signals meant to create belonging ignite divisions, shattering real relationships. Here are the heuristics driving this paradox. Let's rediscover authentic connection.

Below is a deep dive into the complexities of interpersonal communications and the role digital platforms play in the shaping of our networks.

While this is a topic I have given much thought to, and have been immersed in for the better part of the last decade, I defer to the experts referenced within the write up. Nonetheless, please find below the foundational outline for how I think the world works (or how it least functions in the digital realm). Future posts will aim for a 14-17 minute “read time” as opposed to the 44 minute “read time” of this essay.

Because this essay is rather lengthy, I would suggest sharing the link in lieu of sharing by email function. I will not include comment sections on my posts. If you have feedback, please send it to my email (alex@alxpilk.me) or message my profile directly. I promise to respond and acknowledge any emails I receive, especially the criticisms.

Introduction: The Static Cling of Digital Life

The pandemic didn't just send us home; it pushed us into a disorienting digital reality where connection frayed and online friction sparked real-world consequences.

I had been looking forward to the DC Spring in 2020, eagerly anticipating the gentle bloom of renewal after dealing with dead trees for a few months, but in lieu of that, Covid-19 entered the picture and the world abruptly halted. It wasn't a gradual shift, but a jarring, instantaneous transformation. One day, the vibrant pulse of Washington D.C., my new home of a fresh 1 year, buzzed with the frenetic energy of ambition and possibility. The next, it was a ghost town, the constant drone of traffic and street noise was just gone. My first "adult" job, just four months in at that point, was suddenly relegated to my room in a basement of a duplex that overlooked the Pentagon and National Cemetery, the glow of my work laptop screen my new, unyielding companion.

My roommates, promising a fleeting "two-week" escape to the familiarity and safety of their family homes, packed hastily, their farewells tinged with a nervous optimism that belied the growing unease. Eventually, those two weeks turned into months, their absence leaving a gaping hole in my already fragile sense of normalcy. The physical world, once a tangible, vibrant reality, began to recede, replaced by the disembodied presence of the digital. The digital universe, which had been slowly encroaching on our lives, now surged forward with unchecked momentum, accelerated by the relentless drumbeat of the pandemic and its accompanying lockdowns.

It brought about a period an emotionally fueled hypomania – something I had never experienced before and have only experienced one additional time since, I hated the feeling, a strange combination of intense anxiety and intense hyper-awareness. My mind raced, fueled by the unsettling quiet of the city surrounding me and the constant barrage of news, each headline a fresh wave of disorientation. The thought that this was a temporary stop gap and eventually we would return to normal was replaced by a blanket of dread, a sense that we were witnessing a fundamental shift in how we were supposed to navigate and interact with the world. Like an abusive relationship, navigating the online world during this cultural moment of racial unrest, a Presidential election, and a global pandemic fueling an economic question of importance, felt like trying to navigate through a landmine.

Though the silence of the city was deafening, it served in stark contrast to the cacophony of the online world. Social interactions, once anchored in shared spaces and physical presence, now existed solely within the confines of screens, mediated by algorithms and filtered through the lens of of our social networks.. The ease of connection, once a promise of boundless digital community[1], now felt like a fragile illusion, a thin veneer masking a growing sense of isolation and fragmentation.

While I already felt the negative consequences of constant social media use for about 12 years by the this time period, this particular period brought about a new understanding of a phenomenon that social psychologists were already intimately familiary with: the insidious power of dissimilarity cascades. Whether it is due to childhood experiences of using social media without an awareness of politics, or because in its early days social media was primarily used for sharing pictures and life updates, the tools designed to keep us connected through one-to-many communication quickly became a source of division. Social media, which was intended to bring together our unique differences into a cohesive social fabric, soon created a social emphasis focused on disparities over similarities. This result in the gradual or sudden dissolution of existing bonds, leaving behind a pool of colored yarn and a sense of loss.

During this period, the enjoyment I once derived from social media vanished entirely. Although I may have argued before 2020 that I found some level of pleasure in using social media, it became evident that each time I opened Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, I was exacerbating my growing frustration with how social media transformed every interaction into a public debate. However, given the circumstances of social isolation, coupled with a specific frustration towards my libertarian-leaning friends who dismissed online digital interactions as harmless and merely an expression of freedom of association, I came to view this phenomenon as a market failure, which I elaborated on in a blog post.

Social media platforms’ primary method of one-to-many communication via News Feeds, combined with comment sections that devolved into signal and counter-signal warfare, caused our primary space for social interaction to become a cesspool of tribal signaling, with "meme-based morality" enthroned as social law.

A notable instance of meme-based morality arose when I addressed a sentiment that was prevalent during the lockdowns: "People are more important than economics." I articulated that economics is inherently human and critiqued this view as privileged and shortsighted, emphasizing that smaller businesses, typically operated by individuals, were significantly impacted, with many still suffering from the economic fallout today. This perspective and assertion incited a small backlash from some individuals who dismissed economics as immoral, asserting instead that "Empathy matters most. Disagree, then say goodbye."

In response, I decided to send one of the individuals, whom I previously considered a friend, a copy of Adam Smith’s "Theory of Moral Sentiments" and followed up a week later with a copy of Jason Brennan’s “Why Not Capitalism?” This action aimed to potentially shift the discussion offline or allow me to have the final word in asserting my moral high. However, neither book appears to have been read, as that interaction marked our last communication.

Naturally, this was not the first instance of a divergence in our worldviews; rather, it was the final incident that shifted our relationship from friendship to estrangement. Once a dissimilarity cascade begins, it becomes challenging to mitigate and requires effort on both parties. The part of our brain that aims to protect our social status instinctively seeks evidence to reinforce perceived differences, often leading to misinterpretations that confirm this bias toward distinguishing ourselves from those who hold different principles.

Since social media uses a one-to-many communication model, it is challenging to convey messages uniquely to everyone in a network. This, combined with the absence of nonverbal cues such as body language and tone, reduces the individualized connection typically present in face-to-face conversations. The lack of these contextual signals in online communication can lead to individuals interpreting information differently, which may result in misunderstandings and conflict.

Without contextual signals, it’s like people reading the same book but imagining different scenes – one might picture a cloudy day while another sees a sunny day.

Paradoxically, in an age of unparalleled connectivity, reducing exposure to unfiltered opinions may prove advantageous. Given our limited capacity for social processing, the relentless flow of information can overwhelm our ability to engage thoughtfully. Therefore, strategic engagement combined with deliberate curation of our social circles is crucial for preventing dissimilarity cascades and maintaining friendships.

Part 1: Our Social Operating System (And Its Limits)

We're wired for connection like social primates, but our brains have limits. Understanding Dunbar's number and how language evolved as "social grooming" gives us a baseline for our analog needs.

Humans are "social primates." What does that really mean? Essentially, we're evolutionarily hardwired to connect with others and live within communities. Going it alone – through isolation or being ostracized – feels deeply detrimental, likely because connection is fundamental to our survival. Our emotional balance and overall sense of well-being are tangled up with our social bonds, often strengthened simply by being physically present with others. Physical touch itself is huge; right from birth, it plays a key role in our development, helping us build interpersonal skills and allowing us to feel safe enough to form deep connections (Cascio et al., 2019; Gallace & Spence, 2010). The sudden shift to mostly digital interactions during the pandemic really drove this home, leading many to feel "touch starved" and reminding us just how crucial physical presence is for our social health.

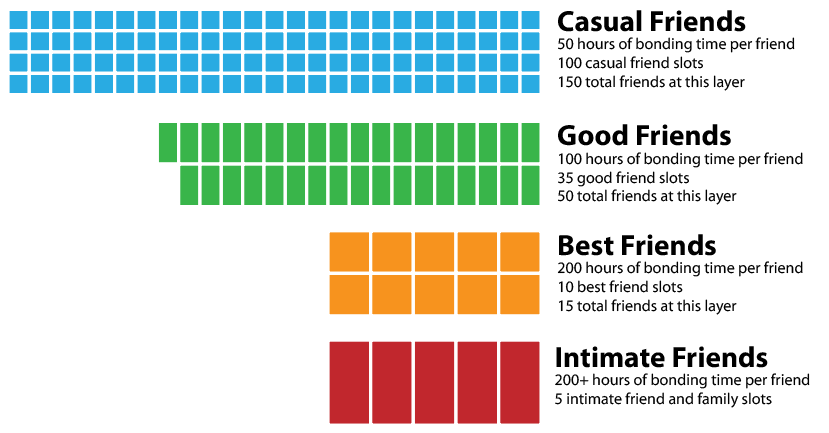

Now, our brains are incredible at processing information, but they do have limits when it comes to social connections. There's only so much capacity we have to actively engage with and keep track of relationships. Anthropologist, Robin Dunbar, famously demonstrated a link between the size of a primate's neocortex (part of the brain) and the maximum number of stable social relationships they can realistically manage (Dunbar, 1998). Applying this to humans suggests a cognitive limit of around 150 individuals – often called "Dunbar's number." Interestingly, this figure pops up repeatedly across different human societies throughout history, from hunter-gatherer groups to Neolithic villages and even modern military units (Dunbar, 1996). Keeping a group of this size humming along requires real social investment (and conformity)1.

For our primate relatives, that investment often looks like hours spent physically grooming each other. Dunbar, in Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language (1996) proposed a fascinating theory: that language evolved in humans as a more efficient form of "social grooming" – for example - "gossip." Instead of picking nits out of each other’s body hair, we use conversation to service multiple relationships at once. In this manner it’s how we share social information, strengthen bonds, and manage our social world much more efficiently than physical grooming alone would allow. Simply put - language isn't just for conveying facts; it's a vital social tool that enables large-scale cooperation and shape complex societies that define us.

Understanding this deep history gives us crucial context for tackling the challenges of our modern digital networks, which we touched on earlier. Sure, digital tools let us stay in contact with way more people than Dunbar's number might suggest, seemingly bypassing our brain's limits. But the kind of interaction we have online often feels worlds away from the rich, nuanced communication (involving both language and physical presence) that our social brains evolved for.

This leads to big questions about how we actually form genuine intimacy and strong bonds today - especially with tools that act like a CRM. To really get into the how building connection – moving from just knowing someone to truly knowing them – it helps to learn about frameworks like Social Penetration Theory put forward by two researchers, Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor.

Onions, Ogres, and Online Oversharing

Building real closeness isn't random; it's like peeling an onion, layer by layer. Exploring Social Penetration Theory and why it seems there are only ogres online.

Back in 1973, social psychologists Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor gave us a foundational map for understanding how relationships get deeper, explaining it as a gradual unfolding of intimacy driven by sharing about ourselves (Altman & Taylor, 1973). Their work focused on how communication acts like the lifeblood, moving connections from just scratching the surface to revealing deep, personal stuff.

It’s interesting that the seeds of our current digital social world were planted around the same time that Altman and Taylor were laying the foundation for their theory about relationship depth. For example, the PLATO computer system at the University of Illinois, initially developed for education, became a testbed for early online community tools like message forums and real-time chat rooms (PLATO History Foundation). Think of them as primitive forms of early social media platforms. I think that the development of tools that enable potentially shallower, wider-reaching connections at the same time as a new theory explaining how and why relationships get deeper really sets the stage for understanding the tensions we face in the social space today.

So, before we dive into how the digital world messes with relationship building, let's unpack Altman and Taylor's original theory (1973). It's built on a few key ideas:

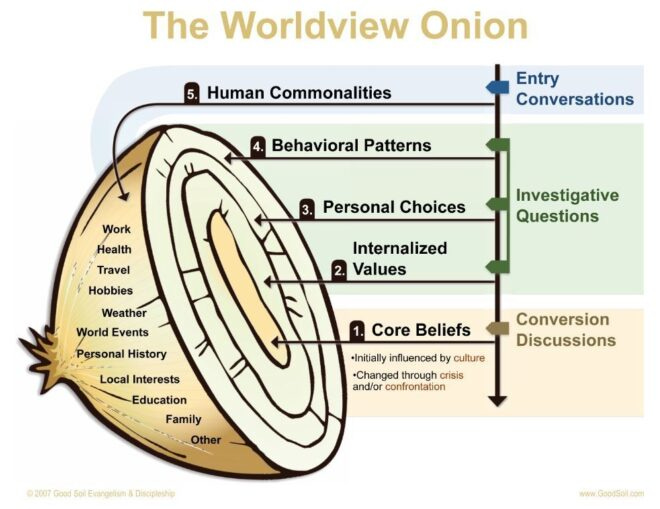

Relationships move from the surface to the core. Think of people like onions (their famous metaphor!). We start conversations with safe, everyday topics (hobbies, the weather) and only gradually peel back layers to share more personal, maybe even controversial things (politics, life-changing moments) as trust builds.

Getting closer usually follows a predictable path. While every relationship is unique, Altman and Taylor suggested there's a general pattern or logic to how intimacy develops. They believed we have sensitive "tuning mechanisms" – we read social cues and adjust how much we share, carefully guiding the relationship's progression.

Relationships aren't a one-way street; they can fade. Things can move backward, too. If conflicts aren't resolved, or maybe if life just pulls people apart and they don't have the bandwidth to maintain the bond, intimacy can decrease. This "depenetration" can lead to distance, estrangement, or the end of the relationship.

Sharing about yourself is key. Self-disclosure – opening up and sharing personal information – is the engine that drives relationships deeper. What you talk about (the breadth) and how personal you get (the depth) pretty much determines how close you can become.

Social Penetration Theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973) often maps out relationship levels based on how intimate the shared information gets. The five commonly identified stages usually go something like this: (1) Orientation, (2) Exploratory Affective, (3) Affective Exchange, (4) Stable Exchange, and (5) Depenetration.

Orientation Stage: Communication is primarily superficial, involving exchanges about safe, conventional topics like the weather, sports, or brief remarks on shared circumstances (e.g., traffic, work). Interactions often follow strict social norms and involve sharing only generic, widely known information, typical of initial encounters with new acquaintances or colleagues.

Exploratory Affective Stage: Individuals begin to reveal more personal attitudes and opinions, expanding beyond superficialities to moderately personal topics like hobbies, travel preferences, or general views on social or political issues. Communication becomes more spontaneous, and casual friendships may form, though many relationships remain at this level.

Affective Exchange Stage: A significant level of comfort and trust has developed. More personal and private matters are shared, including disclosures involving emotional vulnerability. Interactions become more informal, inhibitions lessen, and partners engage in more open expressions of positive and negative feelings. This stage characterizes close friendships and established romantic partnerships.

Stable Exchange Stage: The highest level of intimacy, characterized by deep trust, openness, and predictability. Partners comfortably share their most personal thoughts, feelings, values, and beliefs. Communication is highly spontaneous, and partners possess a strong understanding of each other, allowing for accurate predictions of behavior and emotional responses. This stage represents highly intimate, committed relationships.

Depenetration Stage: This stage involves the gradual withdrawal from intimacy. If a relationship is not actively maintained, or if irresolvable conflicts arise, the breadth and depth of communication decrease. Partners share less personal information, interactions may feel more costly than rewarding, and the relationship progressively fades toward dissolution, sometimes abruptly but often gradually.

When Altman and Taylor (1973) were developing their ideas about relationships, the world operated very differently. Face-to-face was the default setting for communication, rich with all the verbal and non-verbal cues we rely (or avoid). Keeping up across distances meant putting in real effort – writing letters took time and thought, long-distance calls cost money. Communication was slower, with maybe more intentional thought. Those built-in delays likely acted as a natural speed bump, slowing down knee-jerk reactions and preventing the kind of rapid-fire misunderstandings2 ("dissimilarity cascades") that feel so common online today. Finding out what was going on often meant being physically present – at work, the local diner, the library – or checking public postings and often our initial reactions were tempered by our surroundings3.

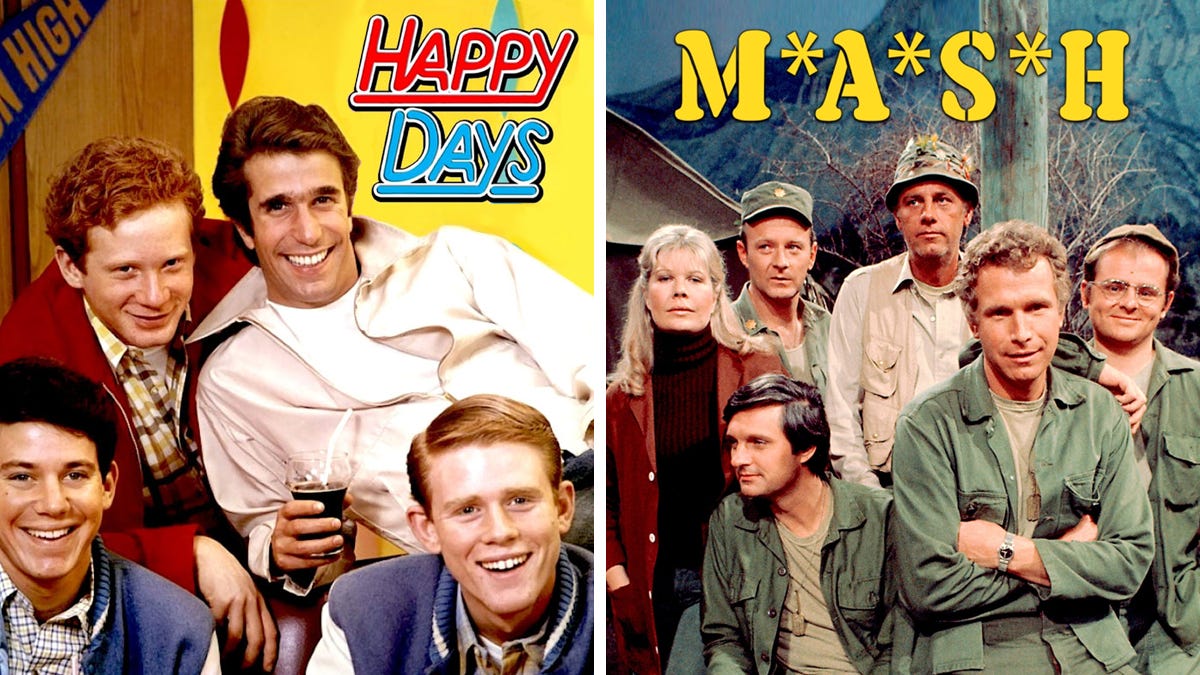

Even early mass media created a different vibe. Think network TV – it gave people shared cultural moments and common topics to chat about, unlike today's hyper-personalized media streams. Radio played its part too. Phones evolved, sure, but even then, connecting involved a different kind of effort and intimacy than the always-on devices in our pockets. Urgent news might come via telegram, a far cry from a nuanced phone call. Privacy felt more tied to physical space and specific channels.

Today's digital world has completely flipped the script. We can share anything, with almost anyone, instantly. This constant connectivity is amazing, but it often feels like too much. Our brains, possibly tuned for managing relationships within Dunbar's suggested limit of ~150 people (Dunbar, 1996), weren't really built for this firehose of interaction and information. The lines between public and private feel constantly blurred and tricky to manage.

Decoding the Digital Divide: Friction, Filters, and Fakes

Today's always-on, overwhelming digital world feels vastly different from the past. Concepts like digital crowding, echo chambers, and rampant misinformation actively disrupt our ability to connect authentically.

So, it becomes pretty clear how today's digital environment throws a wrench into the works of that gradual, trust-building process outlined by Social Penetration Theory. The constant feeling of digital crowding (Joinson, 2011) and the pressure to always be "on" or performing can stifle the vulnerability needed for real self-disclosure – making it tough to move past those early, superficial stages. At the same time, getting trapped in echo chambers or having our views shaped by misinformation makes it harder to develop the mutual understanding required for truly close relationships (the Affective and Stable Exchange stages). The whole idea of building intimacy carefully, step-by-step, through reciprocal sharing faces huge challenges when the online world itself often feels overwhelming, polarized, and untrustworthy. It leaves many of us struggling to find or maintain authentic connections amidst all the digital noise.

To really grasp why things feel so different now, it helps to look back at how people connected before our current digital age, like around the time Altman & Taylor (1973) were first brainstorming their seminal work on interpersonal communications. Back then, the world operated very differently. Face-to-face was the default setting for communication, rich with all the verbal and non-verbal cues we rely on. Keeping up across distances meant putting in real effort – writing letters took time and thought, long-distance calls cost money. Communication was slower, maybe more intentional. Those built-in delays likely acted as a natural speed bump, slowing down knee-jerk reactions and preventing the kind of rapid-fire misunderstandings that feel so common online today4 - leading to a social psychology phenomenon known as dissimilarity cascades (Norton & Frost, 2007)5.

Finding out what was happening locally often meant being there – at work, the local diner, the library, or the town square. Announcements might crackle over a PA system, or you'd see flyers tacked to a real-world bulletin board advertising everything from community events to babysitters and haircuts.

Even as technology advanced, it often brought people together in shared experiences. Think network TV – it gave people shared cultural moments and common topics to chat about, unlike today's hyper-personalized media streams. Radio played its part too. Phones evolved, sure, from party lines to private lines, rotary to touch-tone, but each step still felt different from the constant "on-ness" of the smartphone in your pocket. Urgent news might arrive via telegram, distinct from a nuanced phone call. Privacy felt more tied to physical space and specific communication channels6.

The game has completely changed since the dawn of the digital age. We can now instantly sling information across the globe, reaching nearly anyone, anywhere, anytime. This amazing capability has also brought on a new challenge: we often feel overwhelmed by the firehose of digital interaction. The limits of our own neural systems – possibly wired to handle only about 150 meaningful connections at a time (Dunbar, 1996) – certainly weren’t built to handle this scale. It’s no wonder the lines between our public selves and our private lives feel blurrier than ever in today’s always-on environment, where everyone seems accessible all the time.

Finding ourselves adrift in this overwhelming digital environment, we are continually bombarded with information. This often leaves us feeling stressed out, and we find it more and more difficult to trust the information we see, the platforms we use, or even the authenticity of the interactions we have. Not only is it harder to build deep, individual relationships, but even the very structure of our online interactions seems to be pushing us toward shallow encounters. As we navigate the complex and competing needs of the various associated identities at war in the digital space, we might be wondering how this makes any sense at all.

Instead of a unified digital town square fostering broad understanding, the overwhelm of information, algorithmic curation, ease of finding like-minded niches, and the spread of targeted narratives highlight the inherent tendency toward fragmentation in many online networks. It seems these systems aren’t just accidentally creating friction; they might be naturally optimized for sorting us into distinct, often disconnected, groups. It’s also more difficult to trust the information we see. This tendency towards siloing, where communities form around shared beliefs but struggle to connect or empathize across boundaries, has profound implications for our social fabric. It echoes the ancient story of a tower built not to unite, but ultimately to divide.

Part 2: United We Scroll, Divided We Misunderstand

Sure, we can all post in the same digital square, but algorithms and our own biases mean we're shouting into separate rooms. Unpacking the modern Babel effect of online siloing.

It's easy to feel lost in the static cling of today's digital life, where authentic connection seems constantly disrupted. Perhaps the problem isn't just the volume of noise, but the way the room itself is built – with countless invisible walls sorting us into separate conversations, echoing an ancient story about a tower and scattered languages. This isn't entirely unnatural, of course. Languages always drift and evolve. Think about the differences between American and British English, or even how distinct accents and slang emerge between regions. This happens because language is intensely social. As anthropologist Robin Dunbar pointed out, our brains seem built to handle about 150 meaningful relationships. It’s within these close-knit, Dunbar-sized groups that we imitate each other and develop shared meanings and unique ways of talking. Language naturally adapts to the needs and norms of the immediate community (Oaks, 2015).

The problem is, social media seems to put this natural process on hyperdrive while simultaneously locking us into our specific linguistic bubbles. In the Atlantic, Jonathan Haidt argues that things took a particularly sharp turn around 2009-2012. Platforms dramatically changed the game by introducing features like Facebook's "Like" button (2009), Twitter's "Retweet" (2009), and Facebook's "Share" button for mobile (2012).

Suddenly, interaction wasn't just about direct connection; it became about performance, public endorsement, and the potential for viral amplification.

New online tools, coupled with algorithms created to maximize engagement, unintentionally resulted in a new dynamic that Haidt believes has made social media such a unpleasant place. Research indicated that content that provoked strong emotions, especially anger and disgust aimed at opposing groups, was more likely to go viral. As a result, online incentives were adjusted. Users, driven by instantaneous rewards (likes, shares) and penalties (online criticism, mob pile-ons), taught themselves to perform for their respective audiences rather than participating in the possibly messier, slower process of cultivating authentic understanding across disparities. Conflict became favored over connection in the architecture itself.

Haidt views the biblical story of Babel as not merely an illustration of tribalism but also as proof of the "fragmentation of everything". Not only did this new digital environment, amplified by the changes that occurred around 2011, divide Red and Blue America, but it also divided groups within the left and right, fragments of universities, corporations, professional organizations, and even families. As Haidt states, we have become "disoriented, unable to speak the same language or recognize the same truth," cut off from one another and a shared sense of reality. This deterioration in common comprehension and confidence in institutions makes it virtually impossible to agree on anything in a constructive way and transforms every issue into a fight for survival. The Babel prophecy appears to be fulfilled by the structure of these platforms, which prioritizes viral moments above mutual understanding, as they scatter us into bewildered and frequently antagonistic digital tribes while also giving the impression of never-before-seen connection.

Know Your Nodes: A Field Guide to Social Media Species

From giants like YouTube and Facebook to specialized forums, the social media world isn't one big blob. Here's a quick breakdown of the major platform types and what they're built for.

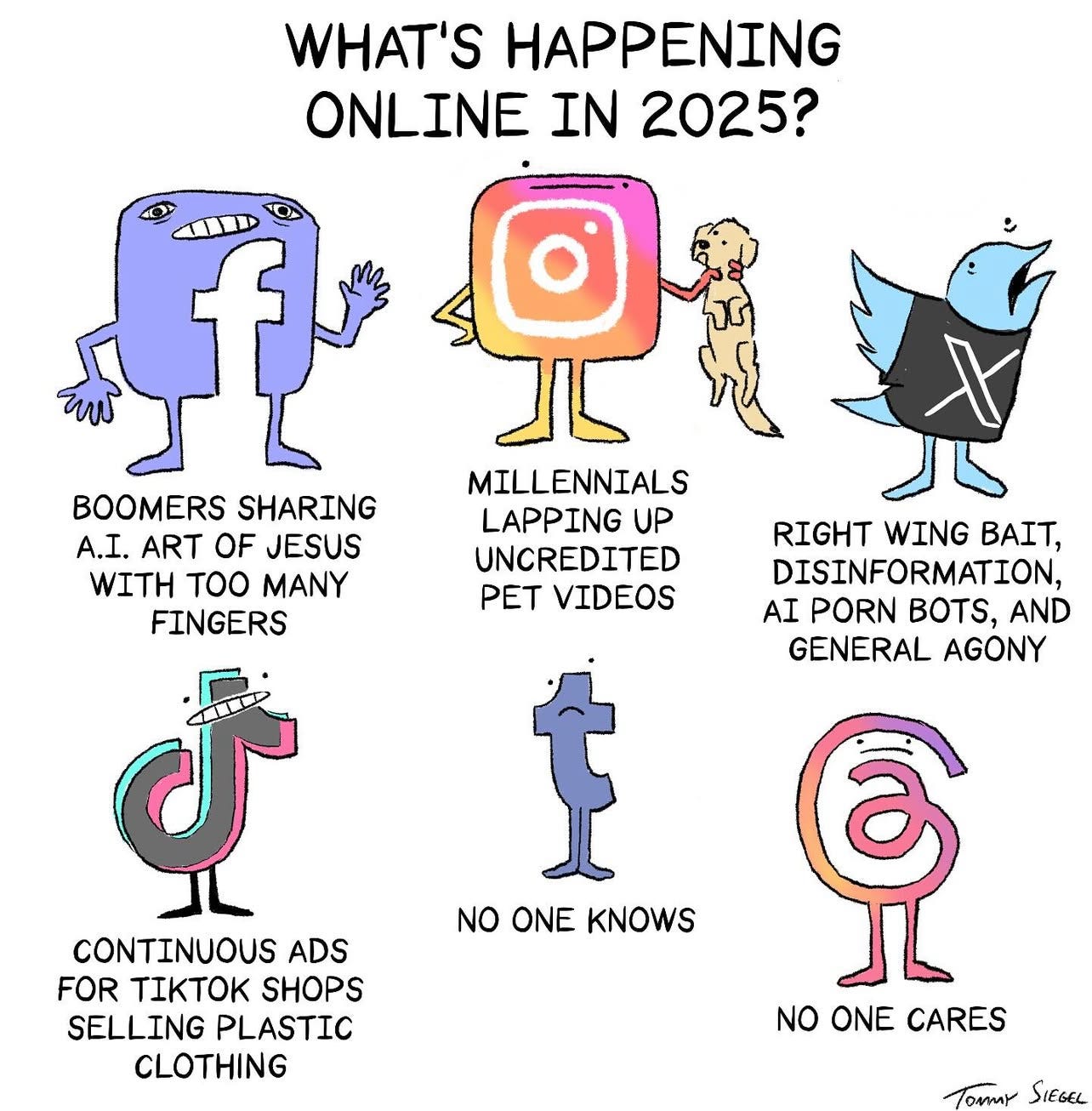

To understand how different online spaces shape our interactions and contribute to the Babel effect, it helps to first map the digital landscape we inhabit. It's a vast territory, but a few dominant players command enormous stretches of it. While things are always shifting, recent Pew Research data confirms that YouTube remains king among US adults (used by 83%), with Facebook still a massive force as well (used by 68%) [Pew Research Center, Jan 2024 cite: 1.1, 1.6, 1.8, 2.1, 2.2, 2.4]. The sheer reach of these giants sets the stage for large-scale communication dynamics, both positive and negative.

But "social media" isn't just one thing; it's a whole ecosystem of different environments, each with its own architecture and purpose. Platforms generally fall into several broad categories, though they often borrow features from each other:

Social Networking Sites (SNS): Think of the classic connection hubs like Facebook. Their main goal is helping you build and maintain your social circle. Key ingredients include user profiles, ways to connect (friending/following), content sharing (posts, photos), and messaging tools. These platforms heavily influence our relationships, how information spreads through networks, and how online communities feel.

Microblogging Platforms: These are built for speed and brevity, like X (formerly Twitter). They thrive on short-form posts, often shared in real-time, facilitating rapid public dissemination of news, political commentary, and reactions to live events.

Content Sharing Platforms: These platforms revolve around specific types of media – think videos (YouTube, TikTok), photos (Instagram), essays (Substack), or music. Core features involve uploading, viewing, and sharing this media, often layered with social elements like comments and likes. They're huge shapers of visual culture, influencing everything from trends and consumer behavior to creative expression.

Professional Networking Platforms: Platforms like LinkedIn are specifically designed for career development and industry connections. Features focus on professional profiles, building networks, job listings, and sharing industry-relevant content. They play a big role in labor markets and how we construct our professional identities.

Messaging Platforms: These focus on private or group communication, like WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger. Key features are instant messaging, voice/video calls, and contained group chats. Their impact is most direct on interpersonal communication and how information flows within private circles.

Community Forums: Built for discussion around specific topics or interests, like Reddit. Features typically include threaded conversations allowing for back-and-forth on specific points, community moderation to maintain norms, and distinct topic-based groups (subreddits, forums). They excel at creating niche online communities and shaping how information spreads within those specialized groups.

Understanding these different designs – whether a platform prioritizes broadcasting (Microblogging), personal connection (SNS), specific content types (Content Sharing), or group discussion (Forums) – helps explain why interacting on TikTok feels so different from LinkedIn, and why the "language" and norms can vary so drastically from one digital space to another.7

Social Media as Silo-Builder

Welcome to the funhouse mirror: Why different online tribes speak different languages and how "selective permeability" ensures we rarely get an accurate picture of opposing views.

So, we have this natural human tendency to form groups and develop unique ways of communicating within them. But layering today's powerful technology on top throws gasoline on that flickering tribal campfire. While social media promises a global village, its actual architecture often excels at building invisible walls, accelerating division rather than fostering broad connection. Platform algorithms, the hidden curators of our online experience, are generally designed for one primary goal: keeping us engaged.

And what keeps us engaged? Often, it's content that confirms our biases, triggers strong emotions (especially outrage), and reflects the viewpoints already dominant within our chosen network. This creates a feedback loop: the platform shows us what we 'like', reinforcing our existing perspective and subtly erecting communication barriers by limiting our organic exposure to challenging or simply different information. We end up with cognitive blind spots that reflect our own group's worldview, making genuine understanding across divides increasingly difficult.

This algorithmic partitioning doesn't just separate us; it fundamentally alters how we communicate, essentially causing different online networks to start "speaking different languages". Key terms central to public discourse – think deeply loaded words like "freedom," "justice," "privilege," "capitalism," or "systemic racism" – take on vastly different meanings, connotations, and emotional weights depending on what group(s) you engage in most conversations on the topics with.

We naturally adopt the framings and definitions prevalent within our own network, because that's the context where they make sense and gain social validation. The result? We might use the identical words as someone from another group, but we're operating with entirely different dictionaries, talking past each other and deepening the very polarization the platforms often claim to overcome. Productive debate becomes nearly impossible when the basic building blocks of language carry conflicting meanings8.

Compounding this "different languages" problem is the profoundly distorted way we often end up perceiving those outside our own bubble. It's not just that we don't hear from them much; it's that what we do hear is often warped. Will Duffield's borrowing of a concept of found in microbiology - "selective permeability", brilliantly captures this dynamic. Our information bubbles aren't hermetically sealed, in actuality they act like biased filters. They tend to block out the reasonable, moderate, or relatable voices from opposing groups, while readily allowing the most extreme, outrageous, inflammatory, or easily mockable content to seep through.

Think about the consequences: if your primary exposure to an entire group of people consists of their loudest, angriest, or most ridiculous representatives cherry-picked by algorithms or shared for outrage clicks, you inevitably develop a skewed and hostile caricature of who they are. This constant diet of distorted "evidence" makes empathy incredibly difficult and reinforces negative stereotypes. It becomes almost impossible to recognize shared values, common goals, or even basic shared humanity when the "other side" is consistently presented as irrational, malicious, or fundamentally alien. Our understanding isn't just incomplete; it's actively shaped by a funhouse mirror reflecting back exaggerated and often false images, further solidifying the walls between our digital silos and making the prospect of finding common ground seem increasingly remote.

Part 3: The Dissimilarity Cascade – When More Connection Means More Division

We've seen how the very structure of the digital world, our modern Babel, often sorts us into separate linguistic and perceptual bubbles. But things get even more complicated when we look at how we actually behave and interact within those spaces. The promise was more connection, but often, the result feels like more division. This isn't just bad luck; it's driven by a fundamental shift in how these platforms are used and the psychological mechanisms they trigger.

We've explored how the very structure of our digital world—its tendency towards fragmentation and the creation of separate linguistic realities, our modern Babel—sets the stage for misunderstanding. But the plot thickens when we examine how we actually behave within these digital walls. The initial promise of social media was a utopian vision of enhanced connection, bridging distances and bringing people closer. Yet, for many, the lived reality feels increasingly like the opposite: a landscape rife with conflict, performative outrage, and deepening division. This isn't merely perception; it's often the direct result of a fundamental shift in how these platforms function and the complex psychological mechanisms they activate within us, leading to what we might call the Dissimilarity Cascade.

The Great Online Shift: From Sharing Life to Signaling Identity

It wasn't always this way. Cast your mind back to the earlier days of social media, the era of early Facebook or even MySpace. For many, their primary function felt genuinely social in the traditional sense: connecting with existing friends and family, sharing photos from vacations or milestones, keeping those real-world ties warm across distances. The communication, while mediated, often retained a personal focus, centered on sharing life events within a relatively known, trusted circle. It felt, perhaps naively in retrospect, like a digital extension of our existing social lives.

But as these platforms exploded in user base and ambition, their nature morphed dramatically. They evolved from intimate-adjacent spaces into sprawling public squares, teeming with strangers, interest-based groups discussing every conceivable topic, and constant, often cacophonous, public discourse. This sheer scale necessitated—or at least encouraged—a significant shift in communication styles. Nuance gave way to brevity (think Twitter's character limits forcing concision, often at the expense of context). Text-based interaction became dominant, stripped of vital non-verbal cues. Visual communication—polished photos on Instagram, rapid-fire videos on TikTok (or even its predecessor Vine) —became paramount, prioritizing aesthetics and immediate impact over reflective dialogue. And the shared language of connection increasingly relied on shorthand: emojis, GIFs, and viral memes became essential tools not just for conveying emotion, but often for signaling group affiliation and demonstrating cultural fluency within specific online tribes.

Crucially, the platforms themselves weren't passive observers; they became active shapers of this new environment. Driven by business models dependent on maximizing user attention, algorithms were fine-tuned to prioritize "engagement" above all else. Unfortunately, "engagement" often translates algorithmically to strong emotional reactions.

Content that sparked outrage, anger, or intense validation proved incredibly effective at keeping eyeballs glued to screens and fingers clicking. Platform features evolved accordingly: "likes" and "shares" became public metrics of social approval and ideological alignment, turning communication into a performance judged by the crowd. Algorithmic sorting began subtly (and sometimes not-so-subtly) reinforcing existing biases and fostering echo chambers where dissenting views were rarely encountered.

Simultaneously, social media transformed into a primary arena for constructing and broadcasting identity, especially political and ideological identity. It became the place to signal your affiliations, perform your virtue, participate in online activism (or its less demanding cousin, "slacktivism"), and consume a steady diet of information validating your worldview. The core function subtly but decisively shifted: from sharing personal experiences to performing a public identity; from maintaining relationships to managing a brand; from connecting with individuals to belonging to a tribe. Add the relentless social pressure in our hyper-politicized climate for everyone to publicly declare allegiance or denounce opponents on every breaking news event, and the conditions were perfect for connection’s promise to curdle into widespread conflict.

Why We Get Pulled Apart Online: The Mechanisms of Division

Understanding why this shift fuels division requires looking at several interconnected psychological and communication dynamics9:

Relationship Rules Revisited (and Broken): Remember Social Penetration Theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973)? Building trust and intimacy involves a careful, gradual peeling of the onion – sharing vulnerabilities incrementally, testing the waters, avoiding conflict in early stages. Online, particularly when the goal becomes signaling virtue or tribal allegiance, this careful process is often trampled. Performative pronouncements, hot takes designed for maximum reaction, and public call-outs replace reciprocal self-disclosure. Vulnerability might still be shared, but often as a performance piece for a specific audience rather than a step towards mutual understanding with an individual. This short-circuiting of the natural stages can prevent genuine intimacy from ever taking root, leaving interactions feeling hollow or transactional.

Mental Shortcuts & The "Other": As discussed in the Babel Effect, our brains rely on heuristics – mental shortcuts – to navigate the overwhelming information landscape online. Confirmation bias makes us readily accept information that fits our narrative, while the availability heuristic might make us overestimate the prevalence of extreme views we see shared frequently. Online, these shortcuts become supercharged. When we primarily interact within echo chambers reinforced by algorithms, our heuristics solidify into rigid assumptions about the world. This directly impacts how we perceive the Out-Group. Will Duffield's concept of "selective permeability" becomes crucial: our bubbles don't just filter out diverse views; they selectively filter in the most extreme, outrageous, or easily stereotyped examples of those we disagree with. We rarely encounter the reasonable majority on the "other side," only the easily demonized caricatures, making empathy seem naive and common ground illusory.

Warped Reflections (Meta-perceptions): It gets even trickier. It's not just our perception of them that's skewed; it's our perception of what they think of us. Research on meta-perceptions reveals a consistent pattern: we tend to drastically overestimate how much members of opposing groups dislike, disdain, or disagree with our own group. Fueled by exposure to conflict-driven online content and skewed samples of the outgroup (thanks, selective permeability!), we internalize the belief that "they" absolutely despise "us." This perceived hostility, even if exaggerated, becomes a powerful driver of actual hostility – what researchers call affective polarization. If you believe the other side fundamentally hates you, you're far less likely to engage constructively and far more likely to reciprocate with animosity. Correcting these inaccurate meta-perceptions, some studies suggest, could be a key to reducing intergroup conflict.

The Misinformation Machine & Brandolini's Law: The digital environment is fertile ground for misinformation and deliberate disinformation campaigns. Troll farms, state actors, grifters, and sometimes just passionate individuals can easily amplify false or misleading narratives, often designed specifically to exploit existing social fissures. This is compounded by what Italian programmer Alberto Brandolini dubbed the "Bullshit Asymmetry Principle" (or Brandolini's Law): "The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it". Creating a compelling lie takes far less effort than meticulously researching, sourcing, and explaining the truth. The ease of hitting "share" further tilts the scales, allowing falsehoods to spread rapidly before corrections can catch up. This constant bombardment erodes trust at multiple levels: trust in news sources, trust in institutions, trust in the platforms themselves, and even trust in the authenticity of everyday online interactions.

Lost in Translation (Communication Style): The very format of much online interaction hinders deep understanding. Asynchronous communication (emails, posts, comments with delayed replies) lacks the immediate feedback loop of face-to-face conversation, making it harder to clarify misunderstandings or gauge emotional reactions in real-time. Text-based communication strips away crucial non-verbal cues – tone of voice, facial expressions, body language – that convey huge amounts of meaning and emotion. This forces us to interpret intent based solely on words, which are notoriously ambiguous. Furthermore, the common one-to-many format (posting to a feed) leads to context collapse: a message intended for one specific subgroup within your network might be seen and interpreted very differently by friends, family, colleagues, or even strangers who lack the shared background or understanding. These factors combine to create a communication environment where misinterpretations are rife and building genuine empathy – feeling with someone – becomes significantly more challenging.

Outrage as Entertainment (Gamified Outrage): Platforms haven't just enabled conflict; they've often gamified it. Algorithms rewarding high engagement often favor posts expressing strong negative emotions, particularly outrage. This incentivizes moral grandstanding (posturing for social approval by expressing exaggerated moral condemnation), performative call-outs, and trolling. Studies have even shown that users who receive more likes and shares for expressing outrage are more likely to express outrage in future posts, creating a positive feedback loop [Brady et al.]. Comment sections frequently devolve into unproductive spectacles of signaling and counter-signaling rather than constructive debate. This "gamification" turns serious issues into points-scoring exercises, further polarizing participants and degrading the quality of public discourse.

The Bitter Harvest: Defining the Dissimilarity Cascade

Putting all these pieces together – the shift from connection to performance, the algorithmic amplification of conflict, the cognitive biases shaping our perception, the inherent limitations of digital communication styles, the relentless spread of misinformation, and the gamification of outrage – reveals the engine driving the "Dissimilarity Cascade." This is the deeply counterintuitive phenomenon where the very technologies designed to increase connection and information flow paradoxically result in the deterioration of relationships and the intensification of social and political division.

MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle, a long-time observer of our relationship with technology, captured much of this dynamic in her book Alone Together (2011). She argued that networked life offers the illusion of companionship without the demands of real friendship or intimacy. We gather thousands of "friends" but might struggle with face-to-face conversation; we prefer texting over talking because it allows us to edit, control, and avoid the messy spontaneity of real interaction. Technology becomes a way to feel connected while remaining safely distant, potentially eroding our capacity for empathy and authentic engagement. This "flight from conversation" and substitution of shallow digital ties for deep bonds creates fertile ground for the Dissimilarity Cascade. When our connections are broad but brittle, lacking the shared history and empathetic understanding built through richer forms of interaction, they are easily fractured by the mechanisms of division that thrive online. The more we rely solely on these mediated, often conflict-ridden channels, the more dissimilar – and antagonistic – we risk becoming.

Part 4: Touching Grass – Cultivating Real Connection in an Age of Division

Fixing our fractured discourse requires more than better tech; it demands cultivating "Madisonian traits" like forgiveness and tolerance. Here's why local communities are the gyms where we strengthen those muscles.

We’ve journeyed through the disorienting landscape of our modern digital lives – the feeling of being perpetually crowded yet strangely alone, the fragmentation of understanding fostered by the Babel effect of online silos, and the downward spiral of dissimilarity cascades fueled by performative outrage and misinformation. It can feel bleak.

If our tools for connection often seem to drive us further apart, eroding trust and making authentic relationships feel like navigating a minefield, what's the antidote? The answer might be simpler, yet more challenging, than we think: We need to consciously step away from the noise and reinvest in the foundations of real-world community. We need, in the parlance of our times, to touch grass.

The Problem Manifested: Bowling Alone in the Digital Dawn

The sense of disconnection and social fragmentation we grapple with today didn't spring solely from smartphones and social media feeds. Political scientist Robert Putnam famously documented a worrying trend starting decades earlier in his landmark book, Bowling Alone (2000). Analyzing vast amounts of data, Putnam showed a steep decline in "social capital" throughout the latter third of the 20th century in America.

Social capital isn't just about friendliness; it refers to the tangible value derived from our social networks – the trust, the norms of reciprocity, the connections that allow communities to function and individuals to thrive. Putnam tracked falling participation in almost every form of civic and community life: fewer people voting, attending public meetings, joining PTAs, volunteering, participating in unions or fraternal organizations, even, yes, bowling in leagues. Informal social connections also withered, with Americans reporting spending less time with neighbors and friends.

Putnam attributed this decline primarily to factors like generational change (older, more civically engaged generations passing), the rise of television encouraging passive, solitary entertainment, and increasing pressures of time, money, and urban sprawl that made participation harder.10 What's fascinating, and perhaps ironic, is that this documented decline in face-to-face community engagement occurred precisely as the early digital communication technologies were emerging and beginning to promise new forms of connection. The late 1990s and early 2000s saw the spread of the commercial internet, the rise of email as a common tool, the advent of instant messaging (AIM, ICQ), and the birth of the first recognizable social networking sites (Friendster, MySpace). While Putnam focused on TV's isolating effects, the seeds of our current hyper-connected, yet potentially isolating, digital world were being sown just as traditional social capital was eroding.

This decades-long trend has culminated in a health crisis now known as the "Loneliness Epidemic." Even before the forced isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic, studies showed alarming rates of loneliness across various demographics. Current statistics suggest around 1 in 3 US adults report feeling lonely, with significant consequences for both mental and physical health. Loneliness is linked to increased risks of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, depression, anxiety, dementia, and even earlier death. While the causes are complex – including economic pressures, changing family structures, and mobility – the decline of robust community ties and the often-superficial nature of purely digital interactions likely play significant roles.

Why Real Places & Civic Virtues Matter

If the digital realm, despite its potential, often exacerbates fragmentation and superficiality, the most potent antidote lies in deliberately cultivating tangible, place-based community. This isn't just about feeling less lonely; it's about rebuilding the social infrastructure necessary for a functioning, pluralistic society. It’s in real-world interactions – in neighborhoods, workplaces, local groups – that we practice the messy, essential work of navigating differences and building trust face-to-face.

Writer and Brookings Institution senior fellow Jonathan Rauch, in works like The Constitution of Knowledge (2021), argues that societies capable of producing reliable knowledge and resolving disagreements depend on adhering to certain rules and norms – a kind of "constitution" for truth-seeking. While his focus there is epistemic, the underlying principles resonate with the broader challenge of social cohesion. He suggests that navigating disagreements productively requires certain "Madisonian traits" or civic virtues – qualities James Madison and other founders recognized as essential for a functioning republic amidst inevitable factionalism. These aren't necessarily about agreement, but about how we disagree. Key among these:

tolerance - accepting the right of others to hold different views

compromise - seeking workable solutions rather than total victory

intellectual humility - recognizing the limits of our own knowledge

And Most Crucially -

forgiveness - the ability to separate the person from the argument

These virtues stand in stark contrast to the dynamics often incentivized online: intolerance, performative outrage, absolute certainty, and personalized attacks.

Rauch, in his more recent work Cross Purposes (2023), specifically explores the role Christianity has historically played in upholding some of these virtues within American democracy, arguing that certain interpretations emphasizing grace, forgiveness, and humility align well with Madisonian principles, while other trends ("Sharp Christianity" or Christian Nationalism) prioritize political power in ways that undermine them. He worries that as traditional religious affiliation declines, society may lose important "load-bearing walls" that historically supported these civic virtues.

The Power of Diverse Communities (Beyond Any Single Tradition)

While Rauch highlights Christianity's historical role, the crucial function of fostering social capital and civic virtue isn't exclusive to any single tradition. The key lies in the power of local, diverse, engaged communities themselves, whether they are faith-based or secular. Sociological research consistently shows that participation in local groups – churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, yes, but also sports leagues, volunteer fire departments, Rotary clubs, book groups, veterans' associations, neighborhood watches, hobby clubs, parent-teacher associations, political party committees, environmental groups, arts councils – builds social capital.

These groups do several vital things that push back against digital fragmentation:

a) Build Trust: Regular, face-to-face interaction within structured groups fosters familiarity and trust among members, even across demographic lines (bridging capital). This generalized trust makes cooperation easier.

b) Foster Reciprocity: Community involvement relies on norms of reciprocity – helping each other out, contributing to shared goals – which strengthens social bonds.

c) Provide Belonging: They offer a sense of identity and belonging rooted in shared activity and place, counteracting the anomie or isolation potentially felt online.

d) Practice Ground for Virtues: These are the real-world arenas where Madisonian virtues get exercised. Working together on a community project, debating a local issue respectfully, organizing an event – these require negotiation, compromise, tolerance for disagreement, and seeing fellow citizens as multi-dimensional people, not just online avatars or enemy profiles. They provide opportunities to practice separating the idea from the person and focusing on common goals.

The key is active participation in groups that require showing up, interacting with diverse neighbors, and working towards common objectives, thereby strengthening the muscles needed for both social cohesion and navigating disagreement constructively.

Moving Forward: Pathways to Genuine Connection

So, how do we translate this understanding into action? "Touching grass" isn't just a meme; it's a prescription for intentional effort:

Cultivate Madisonian Virtues: Consciously try to practice tolerance for differing views (even ones you find repellent), look for possibilities of compromise, acknowledge the limits of your own certainty, and make an effort to criticize ideas rather than attacking people, both online and off. This requires discipline, especially when digital platforms reward the opposite.

Prioritize Embodied Interaction: Make a conscious choice to prioritize face-to-face or at least voice-to-voice communication for important relationships and difficult conversations. Recognize the limitations of text and asynchronous messaging for building deep understanding and empathy.

Engage Locally: Seek out and join local groups that align with your interests or values. Whether it's volunteering, joining a club, attending town meetings, or simply frequenting local businesses and striking up conversations, tangible local engagement rebuilds social capital directly. Find your "third place" – a spot beyond home and work where community happens.

Practice Interpersonal Skills Offline: The skills needed for healthy relationships – active listening, reading non-verbal cues, expressing vulnerability appropriately, navigating conflict constructively, practicing forgiveness – atrophy without use. Seek opportunities to practice these skills in lower-stakes, real-world interactions. Be curious about people, ask questions, and truly listen to the answers.

Mindful Tech Use: While this essay focuses on offline solutions, managing our digital lives is also crucial. This could involve curating feeds more intentionally, setting time limits, disabling notifications, prioritizing synchronous communication, or simply stepping away more often to allow for reflection and real-world engagement.

Rebuilding the robust social connections and civic virtues needed to counteract the fragmentation of our time isn't easy; it requires conscious effort against powerful technological and cultural currents. But strengthening our local communities and reinvesting in the nuanced, demanding, yet ultimately rewarding work of real-world relationships may be the most vital task we face – not just for our personal well-being, but for the health of our shared social and political life.

Conclusion: Beyond Digital Neighbors – Rebuilding Connection in the Noise

We built digital towers but ended up scattered and lonely. Escaping the dissimilarity cascade requires moving beyond clicks and cultivating connection in the physical world.

We began this journey together amidst the eerie silence and sudden digital immersion of the 2020 lockdowns – a moment that felt less like a temporary pause and more like a violent shove into a future we weren't quite ready for. That global crisis acted as a powerful accelerant, turbocharging trends already underway and forcing us to confront the often-uncomfortable realities of our increasingly online existence. It laid bare the profound shift happening in our relationships: a steady drift away from the tangible connections grounded in physical presence towards the more ephemeral, mediated bonds offered by our screens. Looking back, it's clear that this wasn't just about adapting to remote work or Zoom happy hours; it was a crucible moment that revealed deep truths about our social nature and the complex, often contradictory, impact of the technologies we’ve embraced.

At our core, as we explored, humans are social primates, evolutionarily wired for community. Our brains didn't evolve in the isolation of curated feeds but in the dynamic, complex interplay of relatively small, stable groups. Anthropologist Robin Dunbar’s research suggests our cognitive capacity likely limits the number of meaningful, stable relationships we can truly maintain – perhaps somewhere in the ballpark of 150 to 300 people. Within these limits, we developed sophisticated tools for connection: the deep bonding power of physical presence and touch, and the remarkable efficiency of language, which likely evolved as a form of "social grooming" allowing us to maintain larger, cooperative groups than physical grooming alone could sustain. Our social operating system is built for nuanced, embodied interaction within reasonably scaled communities.

Yet, the digital world operates on entirely different principles. It offers the illusion of limitless connection, a potential network stretching into the thousands or millions, completely overwhelming our evolved cognitive capacities. Faced with this information overload and the sheer scale of potential interactions, we inevitably fall back on heuristics – those mental shortcuts essential for navigating complexity. We rely on quick judgments, gut feelings, and signals of group affiliation to make sense of the noise. These heuristics, forming our worldviews, are vital navigational tools, but they also create inherent epistemic blindspots – things we fail to see or understand accurately because they fall outside our familiar frameworks or challenge our group identity. Added to this is the powerful, often unconscious, evolutionary need to signal belonging – to demonstrate our allegiance to our chosen tribes, a drive easily exploited in the performative arenas of social media.

This combination – brains built for smaller groups struggling with digital scale, relying on biased heuristics, and driven by a need to signal tribal identity – creates fertile ground for social fragmentation. As we explored through the lens of the Tower of Babel allegory, the larger and more diverse a group becomes, especially in the disembodied and often anonymous context of online platforms, the more susceptible it is to fracturing. Instead of a unified digital public square fostering shared understanding, we often find ourselves sorted into linguistic and perceptual silos. Platform algorithms, designed to maximize engagement rather than understanding, often reinforce these divisions by feeding us content that confirms our biases and limits exposure to differing viewpoints. Different online communities develop their own "languages," where even common terms carry vastly different meanings, contributing to those epistemic blindspots and making cross-group communication feel like shouting across a canyon. We end up trapped in echo chambers where our view of the "other side" is often a distorted caricature shaped by selective permeability, further hindering empathy and the possibility of finding common ground.

Within this fragmented landscape, the dynamics of online communication often seem tailor-made to generate conflict, fueling the dissimilarity cascades that pull relationships apart. Social media's one-to-many broadcast format makes nuanced, personalized communication difficult; context collapses as messages intended for one audience are interpreted differently by others. The absence of non-verbal cues strips away vital layers of meaning, leading to constant misinterpretations. Asynchronous communication invites misreading tone and fosters anxiety. And the often-toxic environment of comment sections – digital warzones – incentivizes performative outrage, trolling, and tribal signaling over thoughtful dialogue.

All of this directly hinders the kind of gradual, trust-building intimacy outlined by Social Penetration Theory. How can we carefully "peel the onion" and share vulnerabilities (moving past the Orientation and Exploratory Affective stages) when the online environment encourages performative signaling and often punishes authentic expression that deviates from group norms? How can we build the deep mutual understanding characteristic of the Affective Exchange and Stable Exchange stages when echo chambers limit our perspectives and misinformation makes us question the reliability of what we see and hear? The constant digital crowding, the pressure to perform, the algorithmic amplification of conflict, and the erosion of trust create an environment fundamentally hostile to the slow, patient work of building deep, resilient relationships.

The consequences are starkly visible beyond our screens. This erosion of connection contributes significantly to the Loneliness Epidemic gripping modern society. The decline in social capital documented by Robert Putnam in Bowling Alone – fewer community ties, less civic participation, lower levels of trust – seems to have found a powerful, if unintentional, amplifier in our digitally mediated lives. We may have more "connections" than ever, but struggle to find the deep belonging and mutual support that characterize genuine community.

This isn't just a personal tragedy; it's a civic crisis. As we retreat into digital silos, demonize opposing groups based on distorted perceptions, and lose faith in shared truths, the foundations of a healthy democratic society begin to crumble. Productive conflict, negotiation, compromise – the very skills needed to navigate a pluralistic democracy – are undermined by an environment that rewards polarization and tribalism. This necessitates, as argued in Part 4, a resurgence in local civic community – not as a nostalgic retreat, but as a vital space for rebuilding social capital, practicing constructive disagreement, and reaffirming the shared values needed to hold a diverse society together.

So, where does this leave us? It leaves us acknowledging a complex truth: social media is an important tool, arguably the most powerful tool for collaboration and information sharing our civilization has ever invented. It allows for incredible acts of connection, learning, and mobilization. My own experience fixing that TV plug via a YouTube tutorial is a small testament to its practical power. But like any powerful tool, its impact depends entirely on how we use it, both individually and collectively. Its architecture, its algorithms, and the social dynamics it fosters often push us towards shallower engagement, heightened conflict, and deeper fragmentation unless we actively resist those currents through mindful, intentional use.

The path forward isn't necessarily logging off entirely – for many, that's neither practical nor desirable. It's about recognizing the trade-offs, understanding the psychological and social forces at play, and making conscious choices. It's about prioritizing the depth offered by embodied, real-world interaction, even when the breadth offered by digital connection feels easier or more immediately gratifying. It's about cultivating the "Madisonian virtues" of tolerance, humility, and forgiveness in our local communities and offline relationships, strengthening the muscles needed to resist the pull of online outrage and polarization. It's about deliberately choosing to "touch grass," to reinvest in the tangible world and the people who inhabit it alongside us.

Ultimately, the choice is ours. We can continue down the path of increasing digital immersion, accepting the shallow connections, the constant friction, and the deepening silos as the price of convenience. Or we can push back. We can leverage these tools more wisely while actively nurturing the real-world bonds and communities that provide the grounding, empathy, and resilience we need as social primates. We can seek understanding beyond the curated feeds and strive for connection that requires more than just a click or a follow. Because, in the end, while digital platforms allow us to be constantly adjacent, true connection requires something more. As that argument with my friend years ago concluded, the sentiment remains: "I want to be your friend and brother, but we cannot be digital neighbors."

True neighborliness, true friendship, requires sharing more than just a screen; it requires sharing space, time, vulnerability, and the hard, rewarding work of building understanding in the real world.

Author note: explore later this conflicting values

Certainly not always

Whether this is good or bad is up for subjective debate - but it certainly plays on conformity and it’s role in social integration

It's becoming increasingly less costly financially to engage in long term communications with loved ones. However it feels like it's increasingly more emotionally costly as the need to be readily available feels overwhelming. And the delays in communication likely prevented the ever prevalent dissimilarity cascades that we see in interpersonal communications today.

Note: Important timeline relevance with Facebook’s early prominence

Privacy Methods as a future exploration. Private calls. Private letters. Private telegrams. Communication espionage – impact on relationships (grass is always greener). Etc.

So much potential to explore here if we explore niche community traits

And this is just the linguistic division - BEFORE engaging or entertaining the philosophical considerations between the analytical and continental camps.

Each of these could be its own blogpost

Eerily vibes of Farenheit 451 technology